Government Proposal Thoughts

Consultancies Thrive In Difficult Niche Area

December 28, 2025; 8:50 am - Daphne, AL, USA

I do not often write anymore on my trade lane: Government proposal development. I read often of the wiz bang cure-all to lighten your proposal development load. That makes me shake my head. I just want to say the job is complicated. It is very complicated. There are no cure-alls.

There Is Much More To It

No, the wizbangers offering a cure-all do not always offer a solution for every new president. Much of winning is dependent on studied capture melded to the technical solution that blows the evaluators away. That has only a little to do with the proposal team.

It has much more to with the concept of operations (ConOps) and a contract performance team (the companies and the key personnel) that has the best qualifications to do the work on the ground. I will write more on those subjects later.

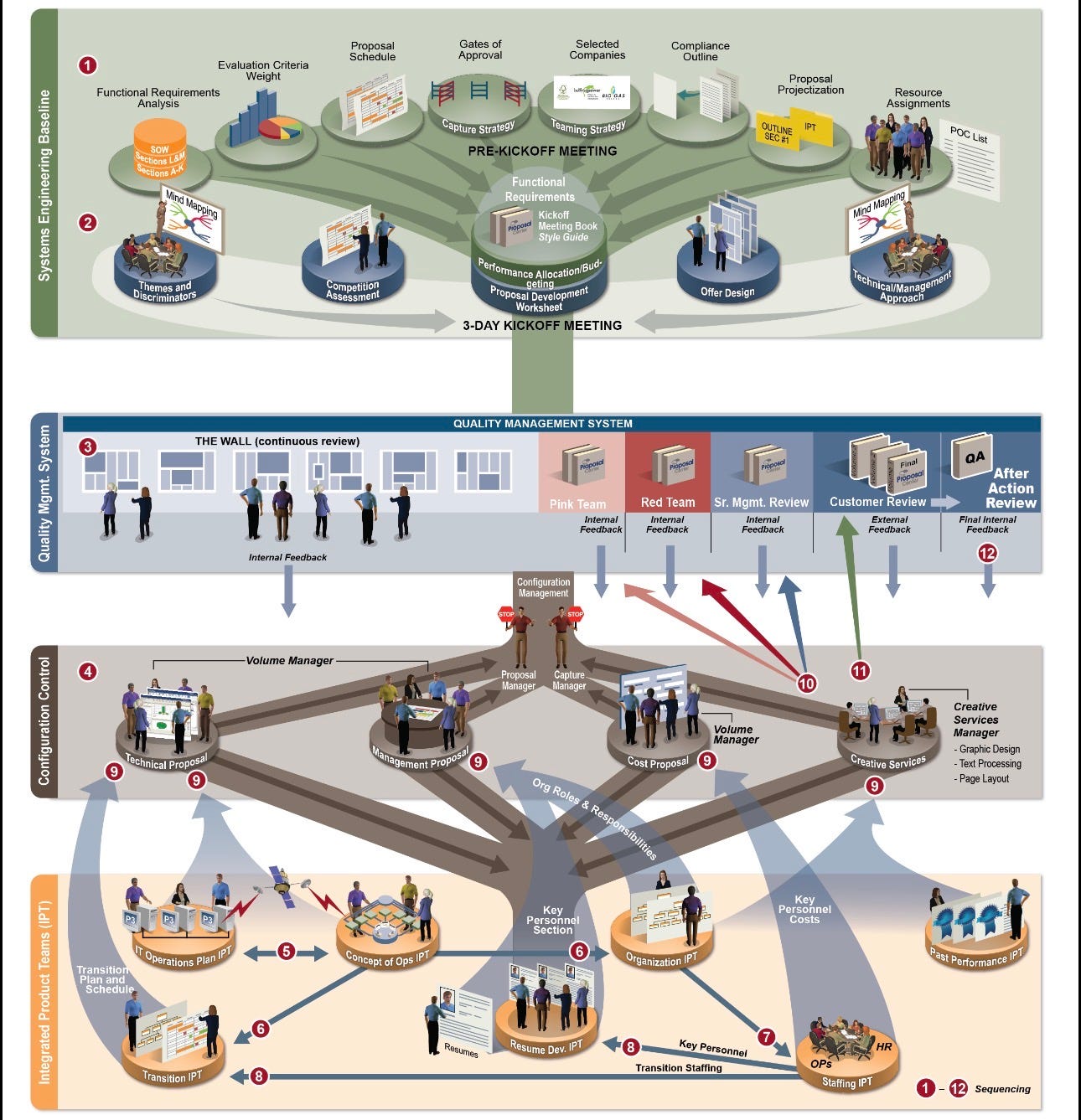

This post is to address that proposals (for government contracts) are a complex undertaking to develop. “Undertaking” is the right word, as it involves scores of processes and subprocesses that can’t be missed. Missing one is deadly. There will be only one winner and 6-8 losers.

While there are processes that can always be improved, few can comprehend just how many subprocesses there are. Fewer still know the type of specialist needed for each proposal development subprocess. I venture it takes 20 years for a solid knowledge base in very aspect of the full gamut, and 30 years to gain noteworthy expertise. By noteworthy, I mean that it is respected by the industry. With that experience in hand, one learns who to call for each type of contract offering. That is called expertise.

Finding That Customer

Proposal team wizbangers try their best to find that uninitiated new leader that just joined the ever-changing C-Suite carousel. Quite often these new C-Suite leaders come not from hiring from within the ranks, but from a line up of retiring general officers—newbies. Now there is a good customer for wizbangers.

That newbie always seems to be the next retired general. Not a one of them has even seen a proposal effort unfolding. That is what always perplexes me. How can you really help them on a proposal? Ever try convincing one that they are out of their element? That takes a careful and a considerate approach. Their brilliance is in other areas, but they can get there.

These babes-in-the-woods often seek a simple solution for a problem of extreme complexity. That is all. Not a one of them can correlate to anything in their work history that is similar to a mega-proposal effort. Think on that a second. When they first confront this new domain, there is a deer in the headlights look. Why?

The closest analogy during a military career is 1) developing, 2) printing, and 3) dropping propaganda flyers on the enemy.

Proposal Complexity Is Unique

Newbies have never led a commercial proposal effort that requires a tightly choreographed series of commercial integrated product teams. There is nothing similar inside of the military. The complexity of the proposal development process is too great for a newly assigned ex-military leader to comprehend in 6 months of study. You can’t tell them that. You work issues with them one at a time and teach what you have learned.

Who Knew?

The person that knew of the knowledge-base deficiency immediately was Tarek Sultan, the chairman at Kuwait’s Agility. Tarek Sultan assumed leadership of what is now Agility Logistics in 1997. He spearheaded the $5 billion, 65,000-employee conglomerate’s worldwide growth through a series of acquisitions. He was smart enough to know in 2006 that a newly retired MG needed to be married to an existing U.S. proposal development apparatus. Tarek had commissioned the U.S. startup of Agility Defense & Government Services (DGS) from scratch in 2006. Tarek had already established Agility as a force in U.S. government contracts in Kuwait and the Middle East. His goal was to take the company into the U.S. and Europe. He did that quickly.

Tarek holds an MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and a Bachelor of Economics from Williams College.

He saw what was needed immediately. Tarek is smart. He bought my proposal development company TechServ Inc. and married us to Agility‘s new DGS startup in the U.S. In the first 3.5 years, we won 42 contracts (66%) worth $10.5 billion. (Agility was then suspended, and I split back off on my own in early 2010.)

Why is it Hard?

A government contract bid is a long project from beginning to end. Shown below, it takes a minimum of 3 years for newbies to get just the basics of a one- to two-year long project. Skill at these BD projects takes much longer, if it ever comes at all. Why?

The BD dance is choreographed. Learning each step takes practice and specialization. The whole BD process from capture to award is a tightly choreographed dance integrating commercial departments and their specialist players.

The handoff of data and intelligence from Capture to the Proposal Team/Apparatus should be a 3-day boot camp of requirements learning and education. It seldom is. The norm is a paltry, and laughable, half-day.

Why Is Learning It Hard?

There is way too much to learn when you do the learning on a part-time basis. You have to do it full time for years. Government proposal development is a career field in a niche market. You grow into learning this niche market, the requirements documents, and its unique lexicon. I started at age 29 and finished at age 70. There was a lot of learning, a lot of starting at the bottom (doing a small business plan) and growing into a volume manager and then a full-proposal manager. That growth step-ladder took me a fully dedicated decade.

Ever see the CEO sit in on a 3-day Red Team? Ever see the CEO sit in on a 3-day Kickoff Meeting? Ever see them lead either? No. You did not. Frankly, they are too busy to learn these processes. They rely on after-action feedback where no one will ever say “The loss was my fault.” Yes, they often don’t get honest feedback. That defeats learning and shortens tenures.

Lasting is Dropping an Anchor

Few of these new leaders last long on the carousel. What anchors them? One thing I see is that a big contract win buys them a longer anchorage. The win proves the wisdom in their being hired, and the hiring executive counsel will seldom admit to a hiring mistake once the big win has been achieved. But 3 years with no results tries the patience of the executive counsel. Win one at 18 months and you are in-like-flint for another 3 years.

Funny how that “big win” works to buy the new president more time at the helm. I have twice helped new presidents last—with major wins landed within 18 months. One was with Pan Am World Services’ Atlantic Underwater Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC) win, the other was with Agility’s Spain Base Maintenance Contract (SBMC) win. Those two huge wins (at different companies) led to tenures of a decade for those two brand-new presidents. I am proud for them.

Thank you for reading, sharing, subscribing, and protesting. I owe you for finding my voice. You have given that place and meaning. I love y’all for that. Please become a subscriber, a paid subscriber if you can.

Nice piece. But I think you failed to mention the importance that integrity commands in your business. You forgot to mention a time earlier in your career. You were volume leader on a multi billion dollar contract for a non-military, yet strategically important, contract of vital national importance. You spent several months applying your vision and process to your volume. For unknown reasons, the company’s newly-appointed President (ex-military general offficer with zero proposal experience) began to meddle (?) in your volume and field of expertise. While respecting your boss’ authority, you made every effort to explain to him the underlying logic and merit of your approach. But, the boss believed he knew better and said it was going to be his way or the highway. As a measure of your integrity, you offered your resignation but left your files and approach in tact—then went on to another effort. Eventually, the boss studied your files, adopted your approach, and went on to win—in large measure because your section was ultimately scored the highest. You kept your integrity in tact, yet left the boss with the tools to craft a winning proposal. It wasn’t only your expertise that won the day—but also your integrity.

Interesting insider info, Carl. As you know, I was a Contract Administrator at one time (for one of the many defense contractors here locally). There’s definitely lots to learn in this area. Smart leaders know what they don’t know—and rely on experts when necessary.